Project Info

Project Description

Despite being a figure of traditional cultural reverence, recognised as the National Heritage Animal, and afforded the highest level of protection under the law, the Asian elephant (Elephas maximus) faces significant challenges in India today. The crux of the problem is one that affects all wildlife in the country: land.

As India’s human population has grown exponentially in the past several decades, so has its demand for resources. At its essence, that demand boils down to the requirement of more land – for agricultural expansion, building roads, constructing dams and railways, and accommodating housing. Consequently, this increased demand for land has resulted in the degradation and fragmentation of the country’s forest cover.

Why did the elephant cross the road? Because we built one across its traditional migratory path, that’s why.

Why did the elephant cross the road? Because we built one across its traditional migratory path, that’s why.

Being a large herbivorous animal, the elephant needs vast areas to roam: browsing, foraging, and moving from place to place in search of food and water with the changing seasons. The ‘home range’ of an elephant herd can vary from an average of about 250 sq km (in Rajaji National Park) to over 3500 sq km (in the highly degraded, fragmented landscapes of West Bengal). Research shows that the more forest habitat is degraded, the farther an elephant herd has to roam in search of food and water.

As elephants are forced to range farther and farther afield, this brings them into conflict with humans. This situation is exacerbated as as humans encroach upon forest areas, planting nutritious crops near forest lands, and building homes, roads and railways. Human-elephant conflict (HEC) is a very serious issue in India today: over 500 human lives are lost in encounters with elephants annually, and crops and property worth millions of rupees are damaged. It is estimated that elephants damage 0.8 to 1 million hectares of agricultural crops (Bist, 2002) every year, and assuming that an average family holds one or two hectares of land, HEC can be said to affect at least 500,000 families!

THE BIG SQUEEZE

India has by far the largest number of wild Asian elephants in the world, estimated at 29,000-30,000 according to the 2017 census, about 58% of the species’ global population. They range in 33 Elephant Reserves spread over 10 elephant landscapes in 14 states, covering about 65,814 sq km of forests in northeast, central, north-west and south India. If that seems like a vast amount of territory, consider that Elephant Reserves include areas of human use and habitation. In fact, unless they lie within existing Reserve Forests or the Protected Area network, Elephant Reserves are not legally protected habitats.

To have elephants in isolated populations, unable to move freely through their home ranges, would have a devastating effect on India’s natural heritage.

A large chunk of the country’s elephant habitat is unprotected, susceptible to encroachment or already in use by humans. While elephant populations are largely concentrated in protected forests in the north-eastern states, east-central India, the Himalayan foothills in the north, and the Western and Eastern Ghats in the south, the animals require free movement (Right of Passage) between these areas to maintain genetic flow and offset seasonal variations in the availability of forage and water.

This is why ‘elephant corridors’ are so important. As forest lands continue to diminish, these relatively narrow, linear patches of vegetation form vital natural habitat linkages between larger forest patches. They enable elephants to move between secure habitats freely, without human disturbance. In many cases, elephant corridors are also critical for other wildlife, including India’s endangered National Animal, the Bengal tiger (Panthera tigris).

WHY SHOULD WE CARE ABOUT WHAT HAPPENS TO ELEPHANTS AND THEIR RIGHT OF PASSAGE?

Elephants are a keystone species and their nomadic behaviour – the daily and seasonal migrations they make through their home ranges – is immensely important to the environment.

Landscape architects: Elephants create clearings in the forest as they move about, preventing the overgrowth of certain plant species and allowing space for the regeneration of others, which in turn provide sustenance to other herbivorous animals.

Seed dispersal: Elephants eat plants, fruits and seeds, releasing the seeds when they defecate in other places as they travel. This allows for the distribution of various plant species, which benefits biodiversity.

Nutrition: Elephant dung provides nourishment to plants and animals and acts as a breeding ground for insects.

Water providers: In times of drought they access water by digging holes, which benefits other wildlife. Furthermore, their large footprints collect water when it rains, benefitting smaller creatures.

Food chain: Apex predators like tigers will sometimes hunt young elephants. Moreover, elephant carcasses provide food for other animals.

The umbrella effect: By preserving a large area for elephants to roam freely, one provides a suitable habitat for many other animal and plant species of an ecosystem.

To have elephants in isolated populations, unable to move freely through their home ranges, would, therefore, have a devastating effect on India’s natural heritage. Many animal species would suffer and the ecosystem balance of several wild habitats would be unalterably upset. It would also eventually lead to the local extinction of India’s National Heritage Animal, one of the wisest and most beloved species on the planet.

SECURING RIGHT OF PASSAGE

[acx_slideshow name=”Right of Passage”]

Elephant corridors are linear, narrow, natural habitat linkages that allow elephants to move between secure habitats without being disturbed by humans.

To secure a future for wild elephants we must ensure their uninterrupted movement between key habitats. To do this, designated corridors must be legally secured and protected. This is what the Wildlife Trust of India (WTI) has been working on through the Right of Passage project under its Wild Lands division for the last decade-and-a-half. Our aim, in partnership with the Government of India’s Project Elephant, the forest departments of elephant range states, and various non-governmental organisations, has been to protect and secure elephant corridors, while simultaneously rehabilitating (and improving the livelihoods of) people affected by conflict in corridor areas.

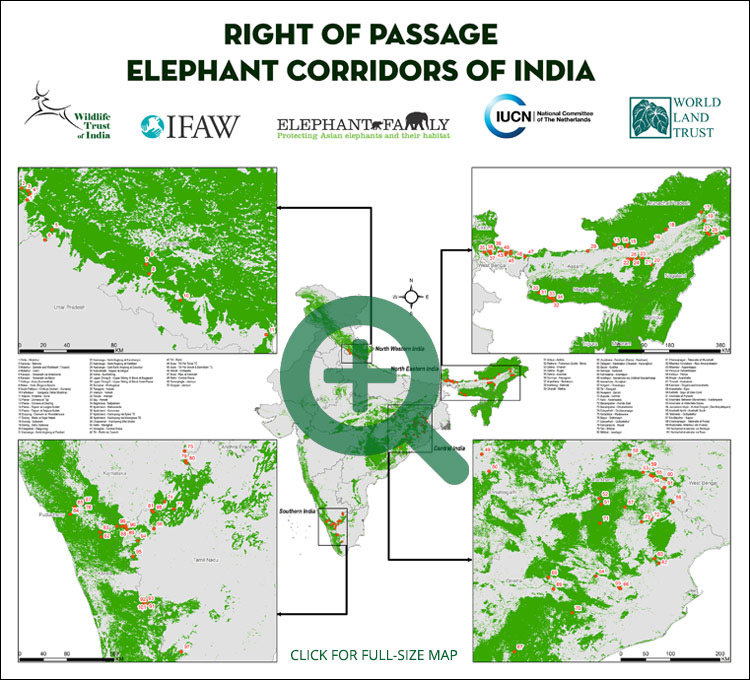

- In 2005, WTI and our global partner the International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW), in collaboration with a team of researchers, officials and NGOs, identified 88 elephant corridors across India, detailing them in a Conservation Reference Series report titled ‘Right of Passage: Elephant Corridors of India’ (see sidebar).

- We systematically assessed and prioritised the 88 identified corridors for conservation interventions and securement, with support from IFAW, the IUCN National Committee of the Netherlands (IUCN-NL), World Land Trust and Elephant Family.

- Since then we have revisited and surveyed India’s elephant corridors once again to update their status and map new corridors. The second edition of the ‘Right of Passage’ publication, now listing 101 corridors is now available (see sidebar).

Over the years, WTI has evolved four approaches for securing and protecting elephant corridors in the country:

- Private Purchase Model: With our implementation partners we directly purchase the land, rehabilitate affected local people, and transfer the land to the relevant state forest department for legal protection.

- Community Securement Model: Community-owned lands are set aside through easements or bilateral benefit-sharing models.

- Government Acquisition Model: The focus here is on policy advocacy work and providing national and state governments with technical assistance and ‘soft hands’ for the acquisition of key corridors.

- Public Securement Model: This model envisages the creation of a network of empowered local stakeholders called Green Corridor Champions that ensure every corridor is monitored in perpetuity. Local communities are engaged through public campaigns and spot interventions.

Corridor Securement: Success stories

Of the 101 corridors identified, six have been secured and six more are currently in the process of being secured through an amalgam of the four models.

| Secured corridors Thirunelli – Kudrakote, Kerala Edayarhalli – Doddasampige, Karnataka Kaniyanpura – Moyar corridor, Karnataka Siju – Rewak, Meghalaya Rewak – Emangre, Meghalaya Chilla – Motichur, Uttarakhand |

Corridors in the process of being secured Kalapahar – Daigrung, Karbi Anglong, Assam Chamrajnagar – Talamalai, Mudahalli, Karnataka Kaziranga – Karbi Anglong, Panbari, Assam Kaziranga – Karbi Anglong, Kanchanjuri, Assam Kaziranga – Karbi Anglong, Amguri, Assam Kaziranga – Karbi Anglong, Deosur, Assam |

The 101 elephant corridors ground-truthed and mapped across India (click to view full-size)

The 101 elephant corridors ground-truthed and mapped across India (click to view full-size)

THE NEED TO UPSCALE

Although an extremely good beginning has been made thus far, with elephant corridors becoming a national policy initiative, all corridors across the country having been documented, and six corridors already having been secured, the rising tide of Human-Elephant Conflict means that there is no time to be lost. We need to upscale our efforts to engage with both the government and corporate India and work concertedly towards our vision of securing all 101 elephant corridors.

The strategic direction for Right of Passage includes:

- Prioritising the securement of corridors that require purchasing of land or setting aside land by local communities.

- Conducting policy advocacy with the Government of India and state governments to allocate resources for corridor securement, and providing them technical assistance and ‘soft hands’ NGO interfaces with local communities wherever appropriate.

- Running a national-level public campaign and setting up a network of Green Corridor Champions (GCC) all across India, thereby institutionalising the involvement of community-based organisations (CBOs) in protecting and securing elephant corridors. GCCs will work in partnership with WTI to sensitise local communities about the importance of corridors and, with the judicious and appropriate use of social, economic and technical interventions, and the vital support of local governments, help in monitoring and securing these corridors.

PARTNERS: Project Elephant, Whitley Fund for Nature and Rohini Nilekani Philanthropies, State Forest Departments.

PROJECT LEAD: Upasana Ganguly