Conservation Convictions

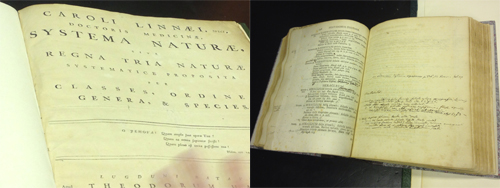

It is holy to hold in ones hand the relics of your religion, the tooth of the Buddha, or the hair of The Prophet or the cloak of an apostle. So it was for me to hold in my hands, ungloved but not unloved, the Linnaen listing of the elephant. The Linnanean Society ( which touts itself as the worlds oldest active biological society having been founded in 1788) in Central London was hosting a lovely reception courtesy the World Land Trust. I had arrived late, having gone through a preparatory runthrough of an evening presentation that I had to give at the BAFTA. A nice posy of nature lovers and donors were sipping on wine and nibbling at the hors d oevers as I entered . ” I can take only two more to the vault,” said John Burton the Founder of the Trust and I jumped ahead of a couple of my Latin friends to take up the offer. Lou Jost from Ecuador joined me.

Photo: Vivek Menon / WTI

Leaving the reception behind we went down to the basement where thorough a metal Chubb door of enormous proportions, inside a humidity controlled room lay the specimens and writings of Linnaeus, the Swedish genius who had started the business of putting the world in order. They have had his treatises in their custody for nearly 200 years, some 1600 books from his library, all the thesis of his students, all his own writings and his collections of specimens, A small lady who could have passed off as a librarian in any part of the world was explaining why the original copy of the Systema Naturae should be handled by hand and not using gloves. They love touch, she said of the books as if they were living pets. ” Luvely” muttered an English lady behind me. I crept between a Dutch and a Belizian conservationist to look at the volume. Looking back to 1753, one could easily wonder why Linnaeus grouped animals as he did; elephants between hippos and pigs; sloths with man and monkey; and the poor pelican along with unicorns, demons and dragons! But the fact that he did try to systematise and explain the relationship of creatures as varied as fungi and fish is something to wonder about.

His description of the Asian elephant, though, was a little controversial.

“I am pleased that the little elephant has arrived. If he costs a lot, he was worth it. Certainly, he is as rare as a diamond,” he wrote in 1753 when a pickled foetus came to him to describe from the collection of King Adolf Frederick of Sweden. He described it as Elephas maximus, the only elephant that he described and said it occurred in Zeylonae paludosis, or Sri Lanka. The African elephant was described later at the end of the eighteenth century but as far as Linnaeus was concerned there was only one elephant. The problem though, was that the pickled foetus that he used as an archetype has now been shown to be that of the African elephant. There were doubts about the foetus as soon as expert scientists looked at it as even morphologically it looked more like what we now know as Loxodonta africana.

Recent protein analysis from the oesophagus of the foetus has confirmed this suspicion. Only one protein in amino acid of haemoglobin is different for the two species; it is aspartate in the Asian and glutamate in the African. Linnaeus elephant had glutamate! So the first elephant that was described by Linnaeus was the African elephant. What a bit of modern forensic detection it took to prove the master wrong.

But master he was and in describing almost everything from fish to insects, plants to mammals, he laid the foundation for the science of taxonomy. In touching his writings and specimens and breathing the musty air of preservation in the society’s strong room, I had satiated an underlying soul-search that I had not known had existed till then.