IFAW-WTI ERN Members respond to bird emergencies during the Makar Sankranti Kite Flying festival at Jaipur

Makar Sankranti is one of the festivals that is celebrated all over India on the same day each year, 14 January, mainly because this is the only festival that follows the solar calendar instead of the lunar calendar. Astrologically, it is the day when the Sun (Surya) enters the Makara (Capricorn sun-sign) and most importantly it marks the change of season, the onset of spring. In most of the states of India, this day is celebrated as either Bhogali bihu (Assam), Lohri (Punjab and most of the northern Indian states), Pongal (Tamil Nadu), Uttarayan (In Gujarat, Rajasthan) or simple Sankrant in Maharashtra, Karnataka, etc.

The season change is marked by a shift in wind patterns which in the past, the farming community used to recognise by flying kites. Today flying Patangs (kite, made of bamboo and paper) has become a mark of celebrations and is very popular in central India. It is this practice that affects wildlife and other living beings (including humans) for whom celebrations turn into mourning.

Kite flying is fun: an object just made of paper and bamboo frame soaring in the sky, under your control destroying any other kites that dare to trespass in its territory! Kai Po Che! (In Gujarati language meaning, I have cut!). Off course, this means in this context is any other flying kite that has been cut by this one! However, does the kite or the tension string, the manja (invariably coated with glass or sometimes even made of plastic) differentiate between a flying inanimate paper thing and an animate flying object: Aves.

Interestingly, the word Kite that is used for Patang, derives its metaphor from a bird, Kite (Milvus migrans sp.) that soars high and hunts its prey from phenomenal heights! However, these same man-made kites, grievously hurt their very inspiration. The entire celebration of Makar Sankrant, in central India, the practice of flying paper kites (and more recently paper lanterns) is turning into a death trap for the species that have ruled the skies before man even existed! The kites themselves are not the problem, but the manja or string used to take the kite up in the sky is the real killer. Usually made of cotton thread on which abrasive substance is coated (mainly a mix of glass and sometimes even steel shavings), the manja is meant to snap the rivals kite, can also entangle a bird, cut its wings and or even neck of people riding bikes with helmets. More recently, a new type of string has come into the picture, locally called, as Chinese manja is a plastic string (similar to the ones used in badminton rackets) that is even deadlier. This has been banned by the NGT along with glass coasted manja.

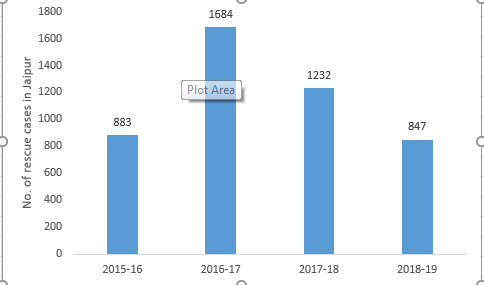

The International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW) and Wildlife Trust of India (WTI) identified this threat as a man-made disaster affecting thousands of birds and decided to respond to it through its flagship Emergency Relief Network (ERN) Project in 2015 in Rajasthan and Gujarat. IFAW-WTI also held two workshops on Avian Rescue and Rehabilitation in Gujarat in 2016 and Jaipur in 2018.

There were many local grass root organisations that were attending to over thousands of birds that were found cut by the manja and had to be rescued. Through its ERN program, IFAW-WTI initially started supporting these organizations financially to meet the increasing costs of medicine, workforce, fuel, and animal care. However, in 2019 IFAW-WTI realised that there has to be more value addition to this work and took the responsibility of this disaster response in the form of executing it under the framework of Best Management Practices.

This year after numerous consultations, deliberations, and inputs from experts of the field during structured workshops IFAW-WTI tested the framework for the Best Management Practices for handling avian emergencies during such man-made disasters. The objective of the framework and the exercise was to develop policies, procedures and systems to handle such emergencies in the most professional, scientific and efficient manner. Under the framework, IFAW-WTI developed the site layout to establish the camp, documentation protocols, treatment and management protocols and most important safety protocols (especially for the rescuers). An Incident Command System (ICS) sheet was developed and displayed to designate the roles and responsibilities of the entire team. ICS included the Incident Commander as the Head of the local organization and a team of personnel ranging from rescuers to veterinarians. The layout used for the camps were based on ideas of human-emergency medical camps with a separate area for admission, triage, minor operation theatre, major operation theatre and recovery room. Extreme importance was given to the triage area to reduce the load on the sterile operation theatre as well ensure complete examination and prioritization of bird to be treated after being duly examined by a veterinarian. Facilities for supportive treatment and pain management were also made in the triage area. A team of five trained veterinarians under the supervision of one medical director was made responsible for the operation theatre that was fully equipped to handle any kind of emergency. Proper documentation of the bird, including the history, nature and extent of the injury and the urgency of the treatment was done prior to sending to the OT. Once surgical procedures were done in the most aseptic conditions a detailed post-operative care datasheet was filled up by the vets and handed over to the respective teams to be taken to the shelter.

During the entire course of the camp, 6000 birds were attended to in Jaipur and Gujarat (Ahmedabad, Porbandar and Bhavnagar). Off these around 60% of the birds were released back to the wild. In Jaipur, the best practices model of IFAW-WTI was implemented in two camps organized in collaboration with the local forest department by Raksha & Hope and Beyond. Two individual ERN members Mr Rushi Pathak (Bhavanagar) and Dr Dhaval Vargiya (from Mokarsagar Wetland Conservation Committee, Porbandar) were supported to hold the bird camps in their respective areas. In addition, support was provided to Jivdaya Charitable Trust (JCT), Ahmedabad to upgrade their operation theatre.