The Leopard’s Lament

By Dr Aaron Wesly

April 12, 2016: It had been a beautiful summer morning at Dudhwa National Park, Uttar Pradesh, and we were almost ready for lunch, when we received an emergency call from Meerut regarding a leopard that had decided to visit the city. Our team had to pack up and leave immediately, with no idea how long it would take to complete the operation. Having recently joined the Wildlife Trust of India (WTI) as a veterinary surgeon and with no prior experience in handling wild carnivore related conflicts, I took along every possible item I felt would be essential to tackle the situation. I even carried some reference material, just in case!

During a melancholic seven hour ride on bumpy roads I found myself imagining the various possible circumstances in which I could be facing a potentially dangerous big cat, drawing from the tales I had read as a child. When we arrived at the Military Hospital in the cantonment area of Meerut city, we met up with the head of our team, Dr Mayukh Chatterjee, who had arrived from Delhi a few hours earlier.

Dr Chatterjee had already cordoned off as much of the area as possible, thereby preventing too large a crowd from gathering in the hospital premises. He briefed us on the situation and we got down to work. I realised soon enough that this was no bloodthirsty beast we were confronted with, but rather a frightened and terror stricken creature that was also perhaps in agony from its injuries, as the blood stained spots on the hospital pavements suggested.

The animal lay atop a thick banyan tree surrounded by open manholes that were completely hidden under a thick layer of fallen leaves. The tree abutted one of the hospital buildings on one side and on the opposite, a ten foot high concrete wall with barbed wire fencing on top. The leopard was probably bleeding, frightened and exhausted from hunger and thirst.

Only a very small portion of its back was visible from about thirty metres away, drastically reducing the chances of a successful darting. Nonetheless, assuming an approximate body weight from the size of its rump, I began calculating the dosage of the tranquilisers to be used. I was in a dilemma – whether to give a higher dose since I was, in effect, responsible for the lives of the people gathered there (including media personnel), or use a slightly lower dose as the animal was possibly in a weakened state. Dr Chatterjee and I finally decided to go with a normal dosage; I prepared two tranquiliser darts and one with half the dose, just in case we needed a top-up.

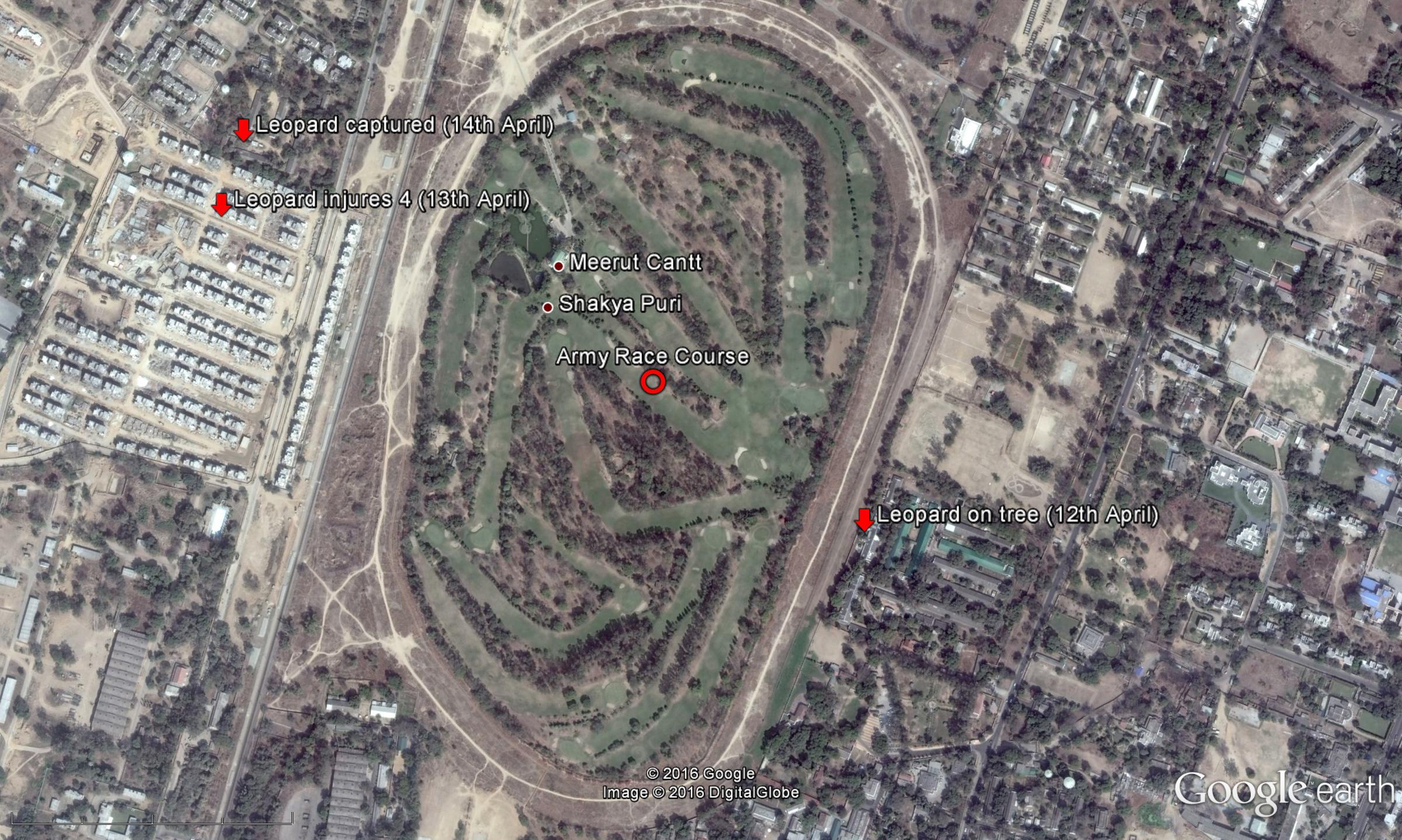

I was not very confident about firing the tranquiliser gun at a target less than one square foot from nearly thirty meters away, so the responsibility fell to Prem Chandra Pandey, a senior team member who has had extensive firearms training in his earlier days. He was right on target with the first dart and we waited for the sedative to take effect. At this moment, despite all our prior warnings, the assembled crowd of media and law enforcement personnel began creating a huge commotion, scaring the partially sedated animal. We were urged to fire the supplementary half dose to completely sedate the animal. Amidst the ruckus the leopard leapt across the boundary wall, instantly disappearing into the darkness of the adjoining Army racecourse.

It is difficult to predict what will happen with a sedated animal running free. It could lie low till the effect of the sedatives has passed and then make a dash for safety. If it falls unconscious in the open, it could get attacked by stray dogs or even humans. If the sedative fails to work due to high anxiety and stress, it could bump into unsuspecting humans and cause severe injuries. Searching for an animal like a leopard, a master of camouflage, was also not something that one could think of doing in the dark. We decided to call it a night, therefore, and went off to get some sleep – somewhere we knew that the next day would bring a lot of toil.

April 13, 2016: The next morning we were informed, to my relief, that the leopard was alive and had been spotted at a construction site about 800 metres from the racecourse. It had probably found a secluded room dark enough for it to feel secure, and had slept through the night. At dawn, unsuspecting construction workers entered the room and were attacked by the equally unsuspecting leopard. Subsequently, at about 8.00am, it injured another two construction workers (part of a mob that attacked it) and escaped into an adjacent compound of the Indian Army’s JCO Mess.

Here the frightened animal had sought out the nearest hiding spot – a large pile of broken furniture on the open veranda of a storehouse. Our team reached the spot at around 8.30am and we could see, from a distance, a portion of its body through the huge stack of furniture.

In my anaesthesia lectures in college I had learned that the after-effect of sedation is an increased level of aggression, but while this leopard seemed calm and hell bent on staying hidden, the fear in the mind nonetheless prevailed. Dr Chatterjee promptly instructed the Forest Department to clear the area of all civilians and move as far back as possible, while a small team would begin cordoning off the area with high nets. The Indian Army proved extremely helpful in this regard, providing us with metres and metres of large nets and heavy metal braces to prop them up against. The local police personnel, under the supervision of the DIG, and Forest Department Officials helped create a semi-circular cordon with the nets, about 15 metres from the storehouse.

Next, the metal braces were slowly moved ahead little by little, until the nets were braced against all openings of the area where the leopard was hiding. This layer was then reinforced with old furniture and more metal braces.

One end of this cordoned off area was darkened with cloth sheets and a trap cage, appropriately camouflaged and baited, was placed. We hoped that the leopard would sense this dark corner as a safer area and would be lured into the cage by the food and water. This entire operation lasted the rest of the day and well beyond sundown. With a small team from the Forest Department assigned to keep watch through the night, we went to rest at around 12.00am.

April 14, 2016: We returned to the site just past 6 o’clock the next morning. The leopard was still in the cordoned area. It had walked into the cage and lapped up every bit of the water, but had not touched the meat and had therefore not set off the trap door.

Our first task was to locate the leopard amidst the furniture and find a possible view to allow for darting. Long bamboo poles were used to pull out pieces of furniture from within the cordoned off area. At 7:30am, with its cover now thinned out, the leopard roared and charged out through the nets. The net cordon held firm. In a frantic bid to escape the leopard lunged through the nets several times at personnel on the other side. Kanpur zoo veterinarian Dr RK Singh, who had shot two darts at the animal, received a nasty gash on his hand in one of these lunges.

While one of Dr Singh’s darts had hit their target, the leopard did not go down, probably because of its excited state. This was my first big learning about conflict situations: even if one delivers a full dose into an animal, it is not necessary that it will get sedated. Sedation time might differ from animal to animal and the circumstances, but maintaining silence is paramount.

At 9.50am our team head fired another dart with a slightly higher dose, hitting the animal on its right shoulder. But the mayhem continued, and the animal did not drop unconscious even after almost forty minutes of waiting! It did however show some signs of sedation, although its head was still up and it looked straight at us through the nets. A last dart with a mild booster dose was fired at around 11.00am, and within minutes the leopard was fully sedated.

The missing second and third distal toes of the leopard

The missing second and third distal toes of the leopard

Once the sedated leopard – we saw that it was a sub-adult male – was placed in the trap cage the situation became utterly chaotic. No barricades could keep the crowds at bay. There were so many people that we could not get near the cage; meanwhile I was getting frantic about the animal’s condition, as protocols prescribed that it should be injected with reversal drugs as soon as it had been confined.

After nearly an hour, the cage with the sedated animal was driven to the outskirts of Meerut city and parked at a petrol pump. Here all civilians were kept at bay; I prepared to revive the leopard while my senior colleagues checked it for any implanted microchips and possible external injuries. Their examination revealed that all the claws on its hind limbs were shattered and two distal digits on its right forelimb had been chopped off. I couldn’t comprehend how this could have happened, but Dr Chatterjee mentioned how the jaw traps deployed in this region commonly resulted in such injuries in leopards. Sadly, because of its permanent disability this animal would never see its natural home again – it would have to be placed in a zoo. To me this aspect alone meant that much of our effort had been in vain, although we did save the animal from being beaten or shot to death.

As I examined the leopard’s heartbeat I found to my surprise that the creature was hale and hearty despite its ordeal. Its breathing was a bit off count, but at a steady pace, and the heart rate had recovered to a completely normal rhythm. Not wanting any complications from delayed effects of the sedative, however, I injected a small dose of the reversal drug soon after all examinations were completed. Within half an hour the leopard awoke, although still dazed and rolling around on its back, trying to catch flowing water with its paws as a member of the Forest Department sprayed water on it. My mind was filled with the memories of all my pet kittens, carefree and enjoying life.

As the leopard was handed over to the Kanpur zoo staff and I bid goodbye to it, I thought to myself, “I see a child who was unnecessarily harassed and harmed by cruel humans – humans who speak about personal space but do not value it.” This leopard had overturned my entire conception of wild beasts, derived from folklore and tales, and I would no longer be able to visualise them as man-eaters or bloodthirsty creatures. To me they are doomed children of nature, and I am proud that I have chosen to fight for their protection and preservation.

Dr Aaron Wesly is an Assistant Veterinary Surgeon with WTI’s U.P. Big Cat Conflict Mitigation Project.