WTI Launches Seminal Conservation Publication Addressing Conflict Between Humans and Big Cat Species in the Dudhwa-Pilibhit Landscape

Based on over six years of on-ground research and conservation action, the report outlines field-proven strategies to mitigate conflict between humans and tigers/leopards in the landscape

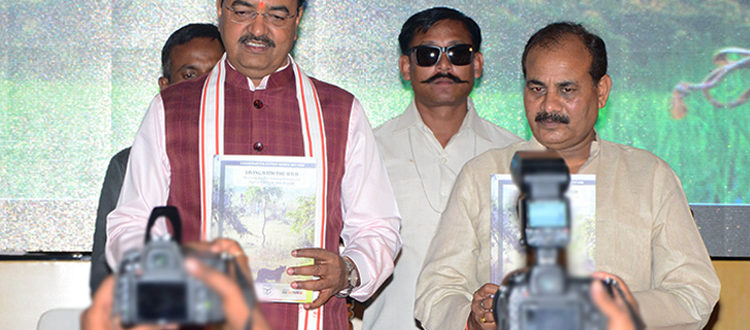

“Living with the Wild”, WTI’s Conservation Action Report on mitigating conflict with big cats in the Dudhwa-Pilibhit landscape, being released by Shri Keshav Prasad Maurya, Hon’ble Deputy Chief Minister, Govt. of Uttar Pradesh (left) and Shri Dara Singh Chauhan, Hon’ble Minister of Forests, Govt. of Uttar Pradesh

“Living with the Wild”, WTI’s Conservation Action Report on mitigating conflict with big cats in the Dudhwa-Pilibhit landscape, being released by Shri Keshav Prasad Maurya, Hon’ble Deputy Chief Minister, Govt. of Uttar Pradesh (left) and Shri Dara Singh Chauhan, Hon’ble Minister of Forests, Govt. of Uttar Pradesh

Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, April 17, 2018: “Living with the Wild: Mitigating Conflict between Humans and Big Cat Species in Uttar Pradesh”, a Conservation Action Report based on the work jointly undertaken by the Uttar Pradesh Forest Department and Wildlife Trust of India (WTI) in the Dudhwa-Pilibhit landscape, was released this morning by Shri Keshav Prasad Maurya, Hon’ble Deputy Chief Minister, Govt. of Uttar Pradesh and Shri Dara Singh Chauhan, Hon’ble Minister of Forests, Govt. of Uttar Pradesh, and dignitaries of the State Forest Department at a workshop organised in Lucknow to discuss possible mitigation or management strategies to reduce the adverse impacts of human-wildlife conflict. The workshop was attended by top officers of the Indian Forest Service from across the country, as well as representatives of various NGO partners.

Based on strategies implemented under WTI’s Terai Tiger Project, the report suggests the possibility of integrating local community volunteers into conflict mitigation activities through the formation of Primary Response Teams

The Conservation Action Report states that around 151 cases of human-wildlife conflict leading to human deaths and injuries were recorded in the Dudhwa-Pilibhit landscape between 2000 and 2013. Of these 73 involved tigers and 63 involved leopards for a total of 136 cases. Interestingly, most attacks on humans by tigers occurred within forests or at their fringes, in particular in sugarcane fields where tigers are now often found to dwell; tigers also did not selectively attack a particular gender or age group, while most attacks occurred during the day time — all of which suggest that the larger proportion of tiger attacks on humans were accidental encounters.

Based on strategies implemented under WTI’s Terai Tiger Project, the report suggests the possibility of integrating local community volunteers into conflict mitigation activities through the formation of Primary Response Teams (PRTs). Prem Chandra Pandey, who heads the Terai Tiger Project and is also a co-author of the report, said: “Community integration and sensitisation is absolutely critical to the long-term management of adverse interactions between humans and big cat species. If local people are not told about the plight of these animals and the drivers of conflict, they will see these incidents in isolation and react accordingly. Communities also need to be educated about certain simple behavioural changes that they can bring about to reduce such negative interactions — for instance, not going into forest fringes or farmlands that abut forests for sanitary purposes and building toilets at home instead.”

“Very simple changes like not leaving children unsupervised near forest edges, or harvesting crops like sugarcane in large groups rather than singly, can bring about a dramatic reduction in the number of accidental encounters with big cats,” he added.

“At a time when wildlife species involved in conflict with humans are invariably portrayed as villains, it is imperative that the true nature of such interactions are brought to public light, and feasible ways to manage human-big cat conflict are worked out”, said Dr Mayukh Chatterjee, Head of WTI’s Human-Wildlife Conflict Mitigation Division and the lead author of the report.

“Most attacks by tigers and leopards are accidental in nature and can be managed provided good public and administrative support is available”, he added. “Crowds of onlookers pose the biggest challenge in most conflict cases, not only putting the life of the animal at risk but also creating the possibility of more (provoked) attacks on people. A scared and cornered tiger or leopard is potentially more dangerous than an animal that has the option to quietly get away. Any animal will do its utmost to save its life; confronting an animal in a conflict situation can cause more human injuries (and possibly deaths), than if the animal is simply allowed to return to the forest.”

“Research undertaken through this project also elucidates various habitat development and management measures that need to be undertaken in order to reduce the number of tigers dispersing out of their source habitats” said Krishnendu Basak, also an author of the report. “Some of these habitat management measures pertain to the reduction of free grazing inside territorial and buffer forest areas, and restoration of critical links that connect various forest patches in this landscape”, he said.

As part of its Terai Tiger Project (run in partnership with the Uttar Pradesh Forest Department and with support from the US Fish and Wildlife Service), WTI operates two Rapid Response Teams in the Dudhwa-Pilibhit landscape, providing the Forest Department with specialised veterinary, biological and sociological assistance in addressing and resolving human-wildlife conflict, especially in cases involving tigers and leopards. The organisation now hopes to be able to replicate the project’s successes across a wider part of the landscape, and perhaps in other states as well.

The UP Conflict Mitigation report being released by the Hon’ble Deputy Chief Minister and Hon’ble Minister of Forests, Govt. of Uttar Pradesh, along with dignitaries of the State Forest Department

The UP Conflict Mitigation report being released by the Hon’ble Deputy Chief Minister and Hon’ble Minister of Forests, Govt. of Uttar Pradesh, along with dignitaries of the State Forest Department

Download the Report

Download the Report